- Home

- Paul Finch

Stronghold (tomes of the dead) Page 9

Stronghold (tomes of the dead) Read online

Page 9

"This is not possible," Gurt shouted. "There should be a carpet of corpses by now. I don't see a single bloody one!"

On the Constable's Tower, Earl Corotocus summoned a nervous squire.

"Take a message to Captain Musard in the southwest tower, boy. Tell him that, Familiaris Regis or not, if he and his men don't start killing these brainless oafs, I'll send them outside with sticks and stones to see if they can do a better job that way."

When the message was delivered, the bombardment on the bridge intensified. The air whistled with goose-feathers. The Welsh crossing over were struck again and again. Dozens more were knocked into the moat, hurtling to its rocky floor, and yet, like those who'd fallen before them, always scrambling back to their feet no matter how broken or mutilated their bodies. They even tried to climb back out, and with some degree of success. A feat that seemed inhuman given that the moat walls were mostly sheer rock.

Ranulf glanced sidelong at his father. Ulbert had lifted the visor on his helmet; always stoic in the face of battle, it was disconcerting to see that he wore a haunted expression.

Many Welsh were now progressing eastwards along the berm, intent on circling the castle and approaching the main entrance at its northwest corner. This meant that the defenders on the curtain-wall were also able to assault them.

Lifting the hatches in the wall walk, they had a bird's eye view of the enemy trailing past below, and so dropped boulders or flung grenades and javelins. It had negligible effect, even though numerous missiles appeared to hit cleanly. The sheer force of impact hurled some Welsh into the river and the current carried them away, though even then they writhed and struggled — albeit with broken torsos, sundered skulls, eye-sockets punctured by arrows. Ranulf saw one Welshman clamber back out from the water, only to be struck by an anvil with shattering effect, blood and brains spattering from a skull that simply folded on itself — and yet he got back to his feet and continued to march. Gurt saw another struck by a thrown mallet; the mallet's iron head lodged in the upper part of the fellow's nose, its handle jutting crazily forward like a rhino's horn — and yet the Welshman, who already looked as if his lower jaw was missing and whose upper body was caked with dried gore, trudged onward.

No agonised screeches or froth-filled gargles greeted the defenders' efforts. There was a sound of sorts — that low moaning, which initially the English had mistaken for the wind. Now that the Welsh were so close, it was clear they themselves were the source of it. But it wasn't just a moaning — it was a keening, a mindless mewling; utterly soulless and inhuman.

At the southwest bridge, more and more Welsh fighters poured over to the other side. Inside the southwest tower, the ballista serjeants yelled at their men until they were hoarse. Bowstrings snapped under the strain and were urgently replaced; the cranks and gears of the war-machines heated and heated until they couldn't be touched. Captain Musard came down again from the tower roof, now frantic. He threw himself to the vents to look out. The enemy should have been lying in heaps on both sides of the bridge. They should have been cluttering the bridge itself. The moat should have been running red with their blood, stacked with their mangled corpses. But it wasn't. Each new salvo darkened the sky. The impacts of missiles slamming into bone and tearing through flesh were deafening. Yet always the Welsh came on. Musard watched, goggle-eyed, as a trio of limping Welshmen crossed the bridge in single file, skewered together on the same length of shaft. He ordered them cut down, butchered. He vowed death for any bowman who failed to strike them. One after another, darts and arrows found their mark, embedding themselves deeply but not even slowing the demonic threesome.

By now, the foremost of the Welsh attackers had reached the point of the curtain-wall where Ranulf, Ulbert and Gurt were stationed.

Ranulf saw one who had lost his left arm, left shoulder and much of the left side of his torso. It had presumably been torn away by a ballista bolt — jagged bones, bloodied and dangling with tissue, jutted out — yet the creature still marched. More to the point, he wasn't even bleeding. The air around him should have been sprayed crimson. Ranulf was so entranced by this unreal vision that when his father clamped a mailed hand onto his shoulder, he jumped with fright.

"Fire!" Ulbert said. "Ranulf, wake up for Christ's sake! We must use fire!"

The call went along the battlements, but only slowly. Barrels of naptha were wrestled forward, but many defenders were in such a daze that they might have tossed them over as they were. Ulbert had to shout to prevent the precious mixture being wasted.

"Timber!" he cried, pushing his way along the walk. "We need timber too, down on the berm. We must form a barricade and ignite it. Bottle them up along the path and we can burn them all as one."

Only a handful of men responded. The others gazed with disbelief at the torn, battered figures below, some disembowelled, their entrails dangling at their feet, others dragging partly severed limbs. Many were human porcupines they were so filled with arrows. Yet they moved on in a steady column.

"Timber!" Ulbert bellowed, having to cuff the men to bring them to their senses.

The only timber available was a derelict stable block in the bailey. Three burly men-at-arms clambered down ladders and broke it up with hammers and axes. Soon, bundles of smashed wood were being hauled up the wall by rope.

"Down there!" Ulbert shouted, indicating a spot about thirty yards ahead of the Welsh force, which at last was being hindered by the avalanche of stones and spears.

The wood was cast down until a mountainous pile had been formed, blocking the berm. Several barrels of naptha were poured onto it, but firebrands were only dropped when the first Welsh reached it. The resulting explosion was bright as a starburst. The rush of heat staggered even the defenders, who were fifty feet above.

Despite this, and to Ranulf's incredulity, the first few Welsh actually attempted to clamber through the raging inferno. A couple even made it to the other side, though they were blazing from head to foot and, finally it seemed, had met their match. First their ragged clothing burned away, followed by their flesh and musculature. One by one, they sagged to the ground. Equally incredible to Ranulf was that none of them tried to dunk themselves in the river, the way he'd seen the French do in their camp on the Adour when the earl had catapulted clay pots filled with flaming naptha right into their sleeping-tents.

Behind this burning vanguard, more Welsh fighters were advancing. Some attempted to circle the conflagration, but again they stumbled into the river and were swept away. Others, at long last, began to display a notion of self-preservation. They halted rather than blundered headlong into the flames and, as Ulbert had predicted, were bottled up along the berm, cramming together for hundreds of yards. Naptha was sluiced onto them all along the line and lit torches were applied, creating multiple downpours of liquid fire. There was nowhere for the Welsh to run to, even if they'd been minded to. Many of them — too many to be feasible — stood blazing together in grotesque clusters, melting into each other like human-shaped candles. The stench was intolerable, the odour of decay mingling not just with the reek of ruptured guts and splintered bones, but with charring flesh and bubbling human fat. Yet only slowly did they succumb, without panic or hysteria, collapsing one by one. Thick smoke now engulfed the battlements, though it was more grease and soot than vapour. The defenders' gorge rose; cloaks were drawn across faces. Walter Margas, his blue and white chevrons stained yellow with vomit, staggered around like a dying man.

When the smog cleared — and it seemed to take an age — all that remained on the path below was a mass of black, sticky carcasses, twisted and coagulated together, yet, unbelievably, bodies still twitched, still attempted to get back to their feet. Unable to see this latter detail, those on the Constable's Tower cheered. They were watching the bluff, where the remainder of the Welsh host was finally holding back from the bridge, perhaps having realised that further attempts to circumnavigate the castle via the berm were futile.

On the curtain-wall ther

e was less euphoria.

"Two hundred," a man-at-arms stammered. "We must have accounted for two-hundred there!"

"And if you times that by how often we killed them, the number should be closer to two thousand," Ranulf replied.

"This is the work of devils," Gurt said, leaning exhaustedly. Dirty sweat dripped from his face. Ulbert too was pale and sweaty, his red and blue tabard blackened with cinders.

"Just be warned," he said. "This isn't over."

"But if that's the best they can do," Gurt insisted, "try to march around the outside of the castle — which must be over a mile — we can attack them with fire all the way. We'll incinerate the lot of them."

" Is that the best they can do?" Ranulf asked. "Or were they just probing? Testing our defences?"

"The latter," Ulbert said. "Now they know that to reach the main entrance, they must first smash the curtain-wall."

"And how will they do that, sir knight?" Craon Culai wondered. He was a tall, lean fellow with a pinched, sneering visage. Captain of the royal men-at-arms, but originally low born, he'd long resented the air of authority assumed by the equestrian class. He lifted off his helmet, yanked back his coif and mopped the sweat from his hair. "Do they command thunderbolts as well?"

He was answered by a deafening concussion on the exact point of the battlements where he stood. Three full crenels and a huge chunk of the upper wall exploded with the force, shards flying in all directions, slashing the faces of everyone nearby. Culai and the three men-at-arms standing with him were thrown down into the bailey, cart-wheeling through the scaffolding, hitting every joist, so that they were torn and broken long before they struck the ground.

It was a dizzying moment.

Ulbert wafted his way through the dust to the parapet and peered across the Tefeidiad. On its far shore, three colossal siege-engines had been assembled, each one placed about thirty yards from the next. Diminutive figures milled around them.

"God-Christ," he said under his breath. "God-Christ in Heaven! The earl's mangonels!"

Ranulf and Gurt joined him, wiping the dust and blood from their eyes. There was no mistaking the great mechanical hammers by which their overlord had shattered so many of his enemies' gates and ramparts. The central one of the three, War Wolf, had already ejected its first missile. The other two, God's Maul and Giant's Fist, were in the process.

Their mighty arms swung up simultaneously, driven by immense torsional pressure; the instant they struck their padded crossbeams, massive objects, which looked like cemented sections of stonework, were flung forth. All of the defenders saw them coming, but the projectiles barrelled through the air with such velocity that it was difficult to react in time.

Ulbert was the first. " EVERYBODY DOWN!"

On the roof of the Constable's Tower, Corotocus and his men moved en masse to the south-facing parapet, drawn by that thunderous first collision. They were just in time to see the next two payloads tear through upper portions of the curtain-wall, fountains of rubble and timber erupting from each impact, a dozen shattered corpses spinning fifty feet down into the bailey. One missile had been driven with such force that it continued across the bailey until it struck the wall encircling the Inner Fort. Huge fissures branched away from its point of contact.

The earl's expression paled, but as much with anger as fear. Blood trickled from the corner of his mouth as his teeth sank through his bottom lip.

"Good… good Lord," du Guesculin said. "They've raided the artillery train. Taken possession of our catapults."

"And how are they operating them, this peasant rabble?" the earl retorted. "Have they engineers? Can they read Latin, Greek… none of my diagrams and manuals are written in Cymraeg, as far as I'm aware."

Had he been on the river's south shore, Earl Corotocus would have had his answer. Already, the three great machines were being primed again. The hard labour — the cranking on the windlass, the retraction of the throwing-arm — was provided by mindless automatons, some in shrouds, others naked, many in rags coated with gore and grave-dirt. They moved jerkily, yet with precision, speed, and unnatural strength. But when there was skilled work to be done — the measuring of distance, the weighing of missiles in the bucket — it fell to three figures in particular.

They too were ravaged husks; heads lolling on twisted necks, gouged holes where eyes had been, organs rent from their eviscerated bodies. Yet Corotocus would have recognised them: Hugo d'Avranches, Reynald Guiscard and, notable in his black Benedictine habit — which now was blacker still being streaked with every type of filth and ordure — the walking corpse of Brother Ignatius.

CHAPTER TWELVE

For the rest of that first day, the Welsh army stood in silence on the western bluff while the three mangonels did their terrible work. Projectile after projectile was launched across the Tefeidiad. One by one, they struck the upper portion of the curtain-wall or its battlements. The only breaks in this pattern came when delays were caused by the contraptions having to be partly disassembled so that they could be moved on their axes to take aim at different sections.

Wholesale damage was caused. Tons of rubble cascaded into the bailey and onto the berm, burying the dead and maimed of both sides. By late afternoon, the English had lost close to forty men, their shattered bodies flung like so much butcher's meat down through the scaffolding. There was no danger of a major breach being caused — the wall itself was nearly twenty feet thick, its outer face shod with granite, its core packed tight with brick rubble, but the position on top of it was becoming untenable.

A message was soon sent to the roof of the Constable's Tower, requesting permission for the south wall's defenders to withdraw to the Inner Fort. It was rebuffed. As the earl's decision was relayed back, another three thunderbolts struck. One passed clean through a gap already blasted in the battlements, ripping the legs off an archer who was attempting to cross the damaged zone via loose planking. Men scattered in front of the other two, but impacts like claps of doom threw out blizzards of splinters and shards, in which twelve more men were slain and twice that many wounded. One lay on the smashed parapet with his belly burst, his exposed guts hanging down the wall like a mass of ropy tentacles.

"Go and talk to the earl," Ulbert shouted to Ranulf as they crouched together. "I'd go myself, but with Culai dead I'm the only one left here with any seniority. Reason with him, plead with him. At this rate, every man on the south wall will be dead by nightfall."

Ranulf had taken his helmet off earlier because it was so dented by repeated impacts. He tried to put it back on, but it would no longer fit. Cursing, he tossed it away, sheathed his sword, slung his shield onto his back and clambered down the scaffolding.

"Ranulf?" his father called after him.

Ranulf looked up.

Under his raised visor, Ulbert's face was smeared with dirt and blood. He wore a graver expression than his son had ever seen. "Politeness costs nothing. Insolence may cost us a lot."

Ranulf nodded and continued down.

In the bailey, it was difficult to work out just how many men lay dead amid the piles of broken masonry. Several of them had been dashed to pieces, their constituent parts mingled in a macabre puzzle of butchered bone and bloody tissue. Father Benan was present. He wore his purple stole and stood with hands joined in the midst of this gruesome tableau. When he heard Ranulf's footsteps, his eyes snapped open. They were wide, rabbit-like; his cheeks were wan with shock, his brow dirty and moist.

"I'd move out of this place," Ranulf said. "There's more where this came from."

"When… when we first arrived," Benan stuttered, "I offered to hear all the men's confessions. But the earl said it wasn't necessary. That we wouldn't be attacked."

"The earl is not always right. It's a pity it's taken us so long to realise that."

"Dear God!" Benan's eyes were suddenly brimming. "To serve Earl Corotocus and die unshriven? That's not a fate I'd wish on anyone."

Ranulf didn't like to dwell on such things

. He couldn't remember the last time he himself had taken confession. "I'm for the Constable's Tower, Father. You should come with me. You're in danger here."

There was a colossal boom as another missile struck the wall behind them. An entire tier of scaffolding fell spectacularly. With a shriek, a man-at-arms fell with it. Benan flinched, but shook his head.

"I must offer a requiem."

"For these scraps of meat?"

"Their souls may yet be saved."

"Father, there are other souls in this castle who could use your prayers. And they still live."

"Go to them. I will join you anon."

Ranulf turned and jogged away up the bailey, though in his full mail it was hot, hard work. He again had to make his way through the Barbican and the Gatehouse, from the tops of which, respectively, Carew's Welsh malcontents and Garbofasse's mercenaries were watching the massed force on the western bluff with a mixture of fear and awe. These two groups in particular faced a dire consequence if taken alive, and the prospect of either that or death suddenly seemed significantly closer than it had done a couple of hours ago.

Ranulf hurried back along the Causeway. By the time he'd climbed to the top of the Constable's Tower, he was streaming sweat and blowing hard. Fresh blood trickled from a slash on his brow. Earl Corotocus was at the south battlements, with various of his lieutenants around him. The rest of his household stood further back, their shields hefted, their weapons brandished. All eyes were fixed on the river's distant shore, and the great war-machines at work there.

"My lord!" Ranulf said, shouldering through.

Corotocus barely glanced at him.

"My lord, you've denied us permission to withdraw from the south wall?"

"That is correct." Corotocus said. He seemed less uneasy than those around him, but there was a tension in his brow. His eyes were keen, blue slivers.

"My lord, you've seen that we're under a very heavy barrage?"

"No-one ever said that fighting the Welsh would be easy, Ranulf."

Stolen

Stolen Dark North mkoa-3

Dark North mkoa-3 Dark North (Malory's Knights of Albion)

Dark North (Malory's Knights of Albion) a collection of horror short stories

a collection of horror short stories Sacrifice

Sacrifice Kiss of Death

Kiss of Death Medi-Evil 2

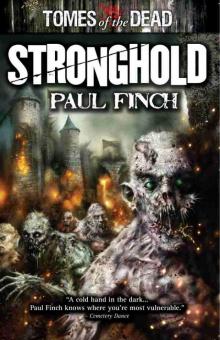

Medi-Evil 2 Stronghold

Stronghold Medi-Evil 3

Medi-Evil 3 Dead Man Walking

Dead Man Walking Strangers

Strangers The Killing Club

The Killing Club Dark North

Dark North A Wanted Man

A Wanted Man Stronghold (tomes of the dead)

Stronghold (tomes of the dead) Hunted

Hunted Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath Stalkers

Stalkers The Burning Man

The Burning Man Medi-Evil 1

Medi-Evil 1 Craddock

Craddock Hunted (Detective Mark Heckenburg Book 5)

Hunted (Detective Mark Heckenburg Book 5) 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories

2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories The Chase

The Chase