- Home

- Paul Finch

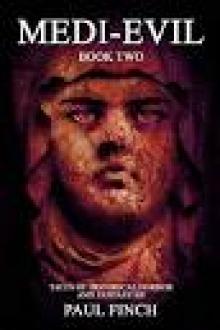

Medi-Evil 1

Medi-Evil 1 Read online

Medi-Evil 1

Historical Horror and Fantasy

by Paul Finch

Published by Brentwood Press

Kindle edition

Copyright 2011 Paul Finch

This ebook is licensed for personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you are reading this book and have not purchased it or it was not purchased for your use only then please return it to amazon.com. and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of the author.

Front Cover image ©iStockphoto.com/duncan1890

Graphics by Eleanor Finch

Contents

The Blood Month

Flibbertigibbet

The Gods Of Green And Grey

Sources

THE BLOOD MONTH

The Battle of Stiklestad, 1030 AD

They were ten-thousand strong, at least. Yet aside from Sveyn’s Danish housecarls, who wore heavy ring-hauberks and full helmets, and who marched in close formation, their razor-honed axes and circular shields to the fore, the bulk of the bonde-army was a motley crew. The chieftains and their personal war-bands – each marked out by its own long-house banner – were mailed and scaled, and carried every arm from the scramasax to the broadsword to the long ash spear; some among them, it was said, being truer to their pagan gods than most, could turn bare-sark in the heat of combat, and slaughter in a red mist of devastation. But beyond these select few, the majority was of ceorlish stock, uplands folk and woodsmen, harnessed with coats of leather and improvised shields. Most were equipped only with knives, mallets and reaping-hooks.

King Olaf’s army, a smaller number by far – three-thousand all told – was more robust, for among its ranks lurked many professional warriors. Aside from Olaf’s hearth-troop, hardened by years of war and plunder abroad, there were also Swedes, Icelanders and Orkneymen; mercenary crews had flocked to the heroic king’s banner even though he was a sworn follower of the White Christ, for a great carve-up of enemy land was promised should the ousted lord wrest back his stolen realm.

Olaf himself, Haraldson by name, ‘the Stout’ by nickname – for the immense breadth of his shoulders and chest – was a distinctive figure. Taller by a head than most men, he was distinguished for his great shield, hammered over with white reindeer hide and inlaid around its central boss with a cross of solid gold, and for the vast white fur of the fairy-bear, which he wore over his layers of iron-ring. But most of all, it was for his fine helmet – also of gold, mounted at its crest with the spread wings of the eagle, and having for a nose-piece the downwards curve of the eagle’s beak.

Olaf now held a central position in his line, between the two great banners associated with his name: the Holy Rood, gold emblazoned on white silk, and, in honour of his sea-roving ancestry, the black raven Land-Waster, embossed on a field of crimson.

None, it was said, could stand against Olaf Haraldson in battle, yet the bonde-army came in a ravaging fury, loathing him for his impressment on them of the Christian gospels, when they still held passions for the martial glories of Odin and Thor. When the two forces clashed, the woods and fells of Trondheim shook. The bonde-host, King Sveyn’s Danes at their front, drove against the Christian wedge like a wave, raining blows with axe and sword. It was a scene of mindless ferocity, the flashing blades hammering on the great bulwark of shields, rending wood and iron, and the flesh and bone beneath. But the assailants always fell back under a storm of missiles, leaving the turf shredded, black with bowels and blood, and strewn with bodies and broken armour.

Between major assaults, the lesser men charged, coarse pagan cries on their lips, “An-A-tan … An-A-Tan … Ygg-Drasil … Ygg-Drasil …” to loose off storms of their own – stones, spears, darts. But Olaf’s men rode out each bombardment, and advanced whenever they could, hacking down these ragged folk and beheading their chieftain, a savage, seven-foot brute named Hrut Viggia.

The heat and stench of it swamped the field – the reek of bones and gore, of guts and mud and seething sweat. The dirge was frightful: a cacophony of screams, shrieks and thundering impacts. Blades rang on bucklers, hammers on helms.

The central melee was a frenzy of murder and mutilation, fearless heroes falling on both sides, though the Christians were now being overwhelmed by sheer numbers. Thord Folason, Olaf’s standard-bearer, raged against the pagans until slashed to pieces. The legendary warrior, Arnljot Gelline, only baptised five minutes before battle commenced, was slain, and alongside him Gauka-Thorer and Afrafaste, and every man of their psalm-singing hearth-troop.

By evening, the Christian host were sorely depleted and had been driven back to their baggage on a grassy slope at the head of the vale. Olaf pointed to the courage of his fifteen-year-old brother, Harald, who stood by his side throughout, until wounded and carried from the field by Jarl Ragnvald. Then, from out the west came a thunder of iron-shod feet. Olaf’s men cheered as over the ridge they saw a mass of advancing warriors. Jarl Dag Hringson and his hearth-troop had arrived; firm allies of Olaf. Though only several-hundred in strength, they circled around the bonde-army and struck it from its flank.

The pagan horde fell back down the churned slope, weary with despair. But one among them refused to quail. Bishop Sigurd, a Christ-priest by name, but also a political creature brought to Norway for his loyalty to Great Canute, over-king of all the Danes, galloped amid their shattered ranks, his purple cloak swirling, calling on their fealty to Odin for a last great assault. And they responded. Remembering how Olaf had cast down shrines to the Allfather, replacing them with churches and demanding that every man hold Sunday in sacred Christian observance, the Nordic wolves went clamouring back to battle.

This time King Sveyn marched at their point, bearing through the crossfire in his heavy black mail, and striking down a Christian housecarl, his broadsword biting helm and skull, brains spurting.

Order collapsed as axes broke shields and lopped limbs, as men fell into the mire rending with fingers at throat and face, stabbing and slashing with daggers, biting, clawing. A war-axe was buried in Sveyn’s shield, a spear-point tore his shoulder. Olaf tried to storm through to him, to butcher this dog who would thwart God’s will, who would restore this reborn land to its ancient beliefs. But try as he might, he was held back, for the bonde-horde was still enough to flood forth in rivers – and now suddenly it was he, Olaf, who was encircled.

As the last of his housecarls perished, he laughed his defiance and dealt out blows to the left and right, but a scent of victory filled the pagans’ nostrils. They pressed harder, striking from every side. When Olaf’s shield was hewn apart, and his sword, Hneiter, broken, an axe smote him on the thigh, shearing the meat and bone, and a second laid open the rings at his back and gashed him the length of his spine. As the great hero dropped to his knees, and slumped backwards over a tooth-like rock, Kalf Arnason came forward and, with the wrath of the bare-sark, plunged his thorny-handled spear into Olaf’s exposed throat.

The news went quickly round the field that the Christian king was dead.

Where Olaf’s standards stood, the White Christ and the Land-Waster still billowing in the July wind, a mob of bonde-men hacked, tore and stamped at a muddied, bloodied figure at their feet – until Thorer Hund thrust his way among them, calling shame on men who acted like scavenging dogs when the prize was a kingly crown.

As though to some whispered command, the Christian force now broke and dispersed over the hillside, triumphant bonde-men swarming in pursuit. In the middle of the field, with ghastly swathes of blood-soaked carnage on all sides, Jarl Thorer pulled down the banners of Olaf Haraldson. Though he couldn’t bring himself to look upon

the Christian symbol, he took the Land-Waster – the blood-red flag with the black raven at its heart – and laid it reverentially over the corpse of Norway’s most admired and yet most detested ruler.

1

The longship rode the wild grey swells with ease. The dragon-carved prow rose and fell with each mountainous wave it crested, the square sail bellying in the hard, cold blasts of the wind. Any normal boat might have turned over and been crushed to matchwood in such a fury of the elements, but this one was constructed in the fashion of the knorrs, its clinker-built hull giving it flexibility as well as strength, its shallow draught allowing it to skip over the raging surf.

Below the after-deck, wrapped in fleeces and huddled amid stacks of cargo – bushels of corn and barrels of iron ore, which the ship’s captain hoped to trade for hides, oil and walrus ivory – there were only two passengers, both of them men. A single lantern swung from the beams overhead, casting a wavering light over the narrow space where they crouched. Without, the ocean boomed, the sea-winds screamed endlessly.

When Ulfketyl, the ship’s navigator, came down from his watch, he grinned as he crawled beside them. Neither passenger greeted him. Ever since they’d left Iceland, he’d proved a nuisance; he was tirelessly inquisitive, filled with mischievous suspicions.

“So … my pretty fellows,” he said, shaking snow from his cloak. The grey beard jutting from under his seal-skin hood was flecked with ice. “How are you finding these fiercest sea-lanes in all of Midgaard?”

“We’ve both of us been a-Viking, Ulfketyl,” the elder of the two men replied. He was called Radnar, and he was massive of chest and shoulder. He wore his jet-black hair and his thick black beard in multiple braids. “We’ve known worse.”

“Worse than this?” Ulfketyl seemed unconvinced. “This is like to the Poison Sea, itself, or didn’t you know?”

“We know,” answered the younger passenger. He was Ljot, and he was fair, both of head and beard. Though of slighter build than the other, he had a look of wiry strength. Like his fellow passenger, his hands and face were crisscrossed by old scars.

“Tell me about yourselves,” Ulfketyl said again. “Where do you hail from?”

“We’ve paid our way twice over,” Radnar said, his voice a menacing rumble. “I thought we agreed no questions.”

If he ever had agreed this, Ulfketyl had forgotten it now. “You’re clearly running from something. And your arms are notched.”

Both Radnar and Ljot had come aboard clad in the mail and leather of the battle-field, and filthied with mud. The broadswords and axes they carried were chipped along their edges.

“We travel to Greenland to spend time with our uncle, whose farm-midden stands at the head of the Snorrifjord,” Ljot replied.

Ulfketyl grinned again. “You seek his protection perhaps?”

“Does it matter?” Radnar said.

The navigator shrugged. “Not to me. I’m a simple sailor. I’m used to minding my business. But there are others in this crew with a mind to speak out should they get wind of … ill-doing.”

“Ill-doing?” The anger showed in Radnar’s ice-blue eyes.

Ulfketyl’s smile narrowed. “King Sveyn of Denmark is offering gold on the heads of all those Christian dogs who stood against him in Trondheim.”

“We know of none,” Ljot replied.

“Is that certain?”

“I’ve told you once. Do you call me a liar?”

The navigator shrugged. “Not at all. But it would sit well with my rowers if I could show them some token of your honesty.”

“You mean a fee?” Ljot said.

“You mean an additional fee?” Radnar added.

Ulfketyl frowned. “Let’s not call it a ‘fee’. Let’s call it … a ‘reward’. For the good will we’ve shown in bringing you to this most wretched corner of the world.”

Radnar leaned back against the bulkhead wall. The swinging lantern cast more shadows. Timbers creaked, outside the waves pounded and crashed. “We’ll discuss it,” he said at length.

Ulfketyl seemed surprised. His smile faded as he shuffled away. But then he stopped and turned. “King Sveyn is also paying out rewards. And those Christian dogs whose whereabouts are revealed to him … they’re facing martyrdom.”

His lip curled, revealing a fang-like incisor, before he made his way out.

Stoically, Radnar lifted his left hand and flexed it. Closer inspection would reveal a livid laceration snaking across the back, from the base of his thumb to the knuckle of his little finger. Crude sutures had been inserted, but it was enflamed, weeping pus and watery blood.

“Do we pay?” Ljot asked.

“Of course we pay,” Radnar replied.

“It’s extortion.”

“And? You won’t catch me dying no martyr’s death.”

“You were ready enough when we arrived at Stiklestad.”

“When we arrived at Stiklestad, Olaf was still alive.”

“And because he’s gone, does that mean your faith has gone too?”

Radnar took a wineskin from a hook beside them. “Enough with this ‘faith’, will you! It’s all I ever hear!” He drank his fill.

“The question stands, brother,” Ljot persisted.

Radnar snorted. “In the old days it wouldn’t have been raised. He who wins the day, wins. At Stiklestad it was Christ or Odin. And Odin won.”

“For now.”

“Hah!”

“Isn’t that so?”

Radnar made no response.

“Radnar … isn’t that so?”

“Yes it is. Whatever you want.”

“You were baptised, Radnar. That means you can’t revert to the old ways, not even if you wish to.”

“I said nothing about reversion. I’m happy as I am.”

Ljot searched for the truth in his brother’s rugged face. “Good. I wouldn’t want to lose my kinsman as well as all my companions.”

“You should be more concerned about yourself. How’s the wound?”

Delicately, Ljot placed a hand against the left side of his ribs. Beneath the leather hauberk and coat of rings, a poultice was held in place by bandages. “The bones are mending, I think.”

“It’s a miracle. A wound like that – I thought you’d be maimed for life at least.”

“So you believe in miracles? That’s something.”

Radnar shook his head at the stubbornness of his brother’s belief.

He himself was less committed to the cause. He wanted to believe in Christ, he wanted to know there would be eternal rewards for embracing those attributes he had once considered worthless and cowardly, though it went against all he’d ever learned. He was ten years older than Ljot, and had been abroad on the Viking trails while his younger brother wasn’t yet weaned from his wet-nurse. He knew the glories of war and conquest, and the seizing of wealth by the force of arms. It wasn’t easy to turn from that. He had done , but only at cost: at cost of his ancestors’ approval; at cost of his seat in the celestial drinking-hall – and that irked him more than anything. Whenever he made the Sign of the Cross, he still, in secret, made the Sign of the Hammer, though he didn’t doubt that he’d lost much of what had once been part of his destiny. And it wasn’t as if the Christ made following Him a simple thing. One of Olaf’s priests had told Radnar that Jesus said: “love your enemies”.

Not your friends – your enemies!

Radnar was still bewildered. To love one’s enemies?

If that was a rule of Christendom, where did he stand – he who had slain enemies in heaps during his former life? He rubbed his aching brow, and thought, for perhaps the hundredth time, how wanting to be a Christian and actually being one were two entirely different things – even for a Christian.

2

They arrived at the mouth of the Snorrifjord a week after the onset of Morketiden, that dread time in the northern lands when winter darkness lasts for the whole day.

The fjord was a great cleft in the tumbling g

ranite walls of the Greenland coast. Beacon fires had been set on its high rocks to provide guidance. Ljot and Radnar, wrapped against the gnawing cold, stood at the prow as Ulfketyl’s crew struck their sails and broke out the oars. Though the passage inland was wide enough for several knorrs side-by-side, it jostled with icebergs and the steersman had to be on his mettle. The brothers watched anxiously as one floe after another slid past in the black, chopping water. To either side, the walls of the canyon rose tier upon tier. Here and there, the frozen arcs of cataracts were visible, zig-zagging down through dark stands of snow-covered pine-forest.

A full day passed – at least it seemed that way, though time was difficult to measure in Morketiden – before they reached the end of the fjord. More lights burned on the shingle shore, though Ulfketyl ran up his peace-signs early and weighed anchor several-hundred yards short, for much of the fjord’s basin was covered with sheet-ice. One other dragon-ship and several fishing boats had been moored at this point, and rode the sloshing waters in bays specially dug out for them.

Now the newly-arrived vessel had dropped its gangplank, dozens of fur-clad folk, many carrying bundles of goods, and with children bound to their backs or chests, made a clamour to come aboard. It was difficult to say how long they had been waiting here, but even more now appeared from the low buildings on the shore, streaming across the ice. The longship would be inundated, so Ulfketyl’s crewmen had to shout and drive them back with sticks.

“You’ll all get passage, so long as you pay,” Ulfketyl snarled down at them. “But we have to unload first. You can be of use to us … we need porters.”

“What is this?” Radnar asked, confused.

Ulfketyl turned to him. “We won’t be outstaying our welcome here. We must re-embark quickly if we’re to reach Iceland before the winter storms blow in.”

“But who are these people?”

“Who cares? There are always folk who seek the Homelands when Morketiden falls. It makes it worth our while: we bring a good cargo here – barley, beer, timber, iron-stone; and take a better cargo back – frightened folk with small baggage and full purses.”

Stolen

Stolen Dark North mkoa-3

Dark North mkoa-3 Dark North (Malory's Knights of Albion)

Dark North (Malory's Knights of Albion) a collection of horror short stories

a collection of horror short stories Sacrifice

Sacrifice Kiss of Death

Kiss of Death Medi-Evil 2

Medi-Evil 2 Stronghold

Stronghold Medi-Evil 3

Medi-Evil 3 Dead Man Walking

Dead Man Walking Strangers

Strangers The Killing Club

The Killing Club Dark North

Dark North A Wanted Man

A Wanted Man Stronghold (tomes of the dead)

Stronghold (tomes of the dead) Hunted

Hunted Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath Stalkers

Stalkers The Burning Man

The Burning Man Medi-Evil 1

Medi-Evil 1 Craddock

Craddock Hunted (Detective Mark Heckenburg Book 5)

Hunted (Detective Mark Heckenburg Book 5) 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories

2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories The Chase

The Chase